Hey Brain Rewirers,

Welcome to this week’s newsletter! Let’s talk about therapy – specifically, EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing) therapy.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing

So, what is EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing)? EMDR is a psychotherapy that helps people process and recover from past experiences1. It is structured so that the patient focuses briefly on a traumatic memory while experiencing eye movements (or bilateral stimulation), which reduces the vividness and emotion associated with the traumatic memory. Therapy sessions typically occur 1-2 times per week, with anywhere between 6 and 12 total sessions. It is structured into 8 phases, which I will list below, but will make more sense after you’ve read the whole newsletter.

- Phase 1: History-taking

- Phase 2: Preparing the client

- Phase 3: Assessing the target memory

- Phase 4-7: Processing the memory to adaptive resolution

- Phase 8: Evaluating treatment results

EMDR was initially introduced in 1989 for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)1. It is guided by the Adaptive Information Processing model2, which is the framework used to explain the clinical symptoms and why EMDR is effective.

Adaptive Information Processing Model

AIP states that to understand incoming stimuli, new experiences are assimilated into existing memory networks2. So, when someone hands you a cup, because you have previous experience with cups, you know how to hold it. But if you hand a baby a cup, they will probably hit it against something, or turn it upside down, or bite it. Because so far in life, they’ve been given toys and bottles and not cups, so it does not fit into an existing memory network. In a similar tone, a failed love experience will be assimilated into memory networks about relationships, and inform expectations and warning signs for future relationships.

When an individual has a new experience, it needs to be processed for useful information to be learned and to be stored with appropriate emotions to guide future activity2. However, this processing does not always happen. We can take a simple example of a child falling off a bike. If they are comforted and nurtured, the fear of getting back on a bike will eventually pass, and the child will learn how to ride a bike more successfully. The new experience was appropriately processed. However, a different child might become anxious about bike riding, and the fear never passes. This shows that the information processing system stored the experience without processing it, so the only memory of riding bikes is fear, not any enjoyable bike rides or any memory that eventually the pain subsided.

Storing information without appropriately processing it lays the foundation for dysfunctional responses to similar future events. Therefore, the model guiding EMDR views current situations that are distressing as a trigger for a past, unprocessed incident2. And we don’t even need to be able to remember the traumatic event for it to cause dysfunctional responses.

A Side Note on Trauma

I said that EMDR was originally developed to be used with people living with PTSD. That’s true – but why has there been a change? Well, to be diagnosed with PTSD, you had to have a specific ‘trauma’ occur. The traumatic event must involve actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence3. However, the symptoms of PTSD can occur even following life events that do not meet that criteria. The COVID-19 pandemic is a great example of this, and this pandemic has actually reignited the debate4 about whether the criteria for defining a traumatic event should be broader.

EMDR is no longer used only for PTSD because it has been noted that even in people who do not meet the criteria for PTSD, EMDR remains effective at alleviating symptoms. Shapiro gives a great example in his seminal 2007 paper2:

Imagine the sudden death of a man's wife of 30 years. Following her death, he has intrusive thoughts, depression, and sleep disturbance. That could be diagnosed as PTSD. However, if instead of the wife dying, she ran off with her dance instructor, the man could no longer be diagnosed with PTSD, even if he has the same symptoms. Shapiro calls these events which do not meet the criteria of PTSD “small t” traumas, not because they are less traumatic, but because they are more prevalent. They are life events.

Why Does EMDR Work?

Neurobiological studies suggest that such dysfunctional experiences are stored in implicit and episodic memory5,6. Implicit memory enables us to ride a bike after a 10-year break; the muscle sensation is stored in memory. But, if physical sensations which aren’t useful (the memory of being bullied in school or yelled at by a teacher) get stored, it can lead to dysfunctional responses in the future. And so your past becomes your present.

EMDR procedures were developed to access the dysfunctionally stored experience and stimulate the processing system, so the information can achieve an adaptive resolution, being integrated from an implicit memory to an episodic memory (‘just an event’) and even semantic memory (‘just a story’), without storing the negative physical sensations.

Eye movements have effects on memory retrieval, reduction of negative emotions, imagery vividness, and attentional flexibility7. There is evidence that the number of eye movements made while viewing a picture correlates to the memory of that picture8. There are also strong connections between the hippocampus, our memory center, and oculomotor movements (eye movements)9. Finally, there is evidence that bilateral eye movements enhance the retrieval of episodic memories10.

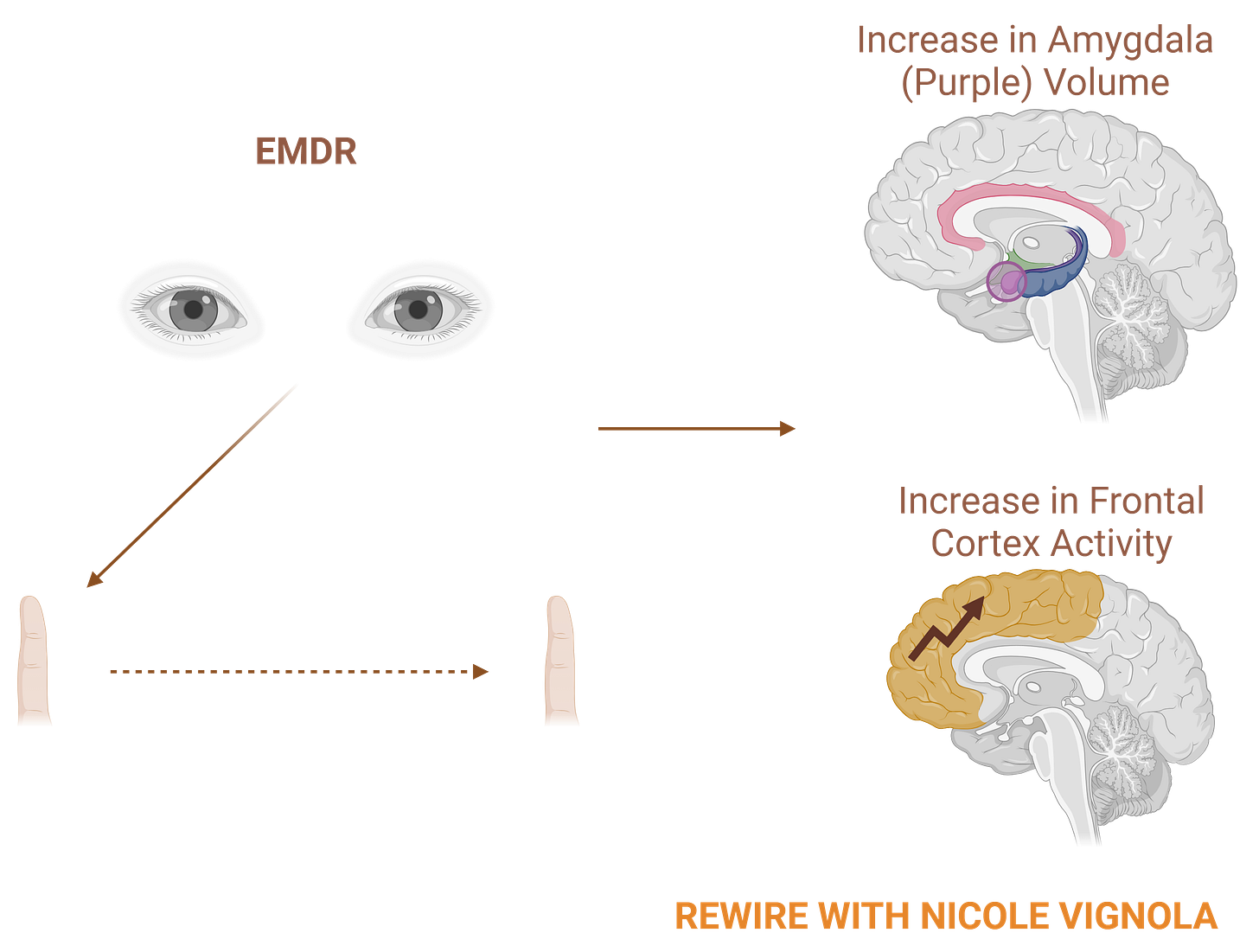

A number of neurobiological studies have shown changes in brain processing post-EMDR, coinciding with the alleviation of symptoms. A brain imaging study11 showed that during EMDR sessions, there is higher activity in the orbito-frontal, prefrontal, and anterior cingulate cortex (known for reasoning, logic, attention, and emotional modulation). This means that the traumatic events are being processed at a cognitive level during EMDR11. Another brain imaging study found that following EMDR, volumes of the amygdala increased, suggesting greater emotional processing12. Studies have also shown that EMDR therapy normalises the default mode network, which is in charge of self-reflection, memories, and introspection13.

What if You Don’t Have Trauma?

What we learn from studies about EMDR and Trauma can still be applied to everyday life!

- Sometimes events from our past that we don’t even remember can still affect our present!

- Our thoughts and beliefs about ourselves may also be based on previous events which lead us to repeat actions that confirm these beliefs. Our pre-defined beliefs may not serve us.

- Our brain can adapt! EMDR is proof that our brains can change.

- There isn’t always a secret pill to fix everything. EMDR therapy is relatively short, but still requires effort.

- Our eye movements are maybe more important than we think!

- We know that panoramic vision (looking at a wide-open space) can lead to a reduction in stress and anxiety and improve problem-solving14,15

Until Next Week,

Nicole x

P.S. Leave a comment with requests for future newsletters!

References

EMDR, adaptive information processing, and case conceptualization.

Distinct roles of eye movements during memory encoding and retrieval - PubMed

Eye fixations and recognition memory for pictures - ScienceDirect

An Anatomical Interface between Memory and Oculomotor Systems - PubMed

Bilateral eye movements enhance the retrieval of episodic memories - PubMed

Neurobiological Correlates of EMDR Monitoring – An EEG Study - PMC

Amygdala Volumetric Change Following Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - PubMed

Hi Nicole, I have just finished your Rewire book and I wanted to thank you for three main learnings for me: 1) the section on creeping normality was very interesting as I suffered from a lot of rejection and bullying in my youth and still do today. I was born with a lazy eye and have had corrective eye surgery twice as a child, however I was told that the result of the surgery was a big improvement but not perfect, however it was the best they could do. I’m 61 now and still have vivid memories of this conversation when I was 10. 2) The chapter on Fixed vs Growth Mindset was great and I learned that I have a very closed mindset and confirmed by my wife. 3) I found the section on building self trust excellent.

I was hoping that you might be able to offer some guidance on rewriting my narrative for someone who suffered and still suffers from micro traumas, with my small physical defect. I try daily meditation, however I’m not fully ready to accept my physical appearance and find it difficult to let go of constant resistance.

I was hoping you could offer some advice in your regular articles or perhaps you offer individual coaching.

I look forward to hearing back from you and wish you continued success in 2025.

Regards

John Garland